“BE PREPARED” is the sensible motto of the boy scouts. Yet the fast spread of covid-19 reveals that the world largely ignored that wise dictum. With one conspicuous exception that we shall explain, most countries didn’t have adequate plans or stockpiles for confronting a pandemic.

That was despite ample warning. The Spanish flu in 1918-20 killed around 50m people globally. And a long list of epidemics has marked our own day. AIDS, identified in 1981, has killed tens of millions of people. “Mad cow disease” (bovine spongiform encephalopathy) emerged in 1996, from which no patient has recovered. Then there was SARS in 2002–03; the H1N1 “swine flu” in 2009; MERS in 2012; and the Ebola outbreaks in 2014 and again in 2018. We should have expected more such epidemics, because new diseases of humans keep arising from diseases of animals with which we have close contact.

Although several East Asian countries reacted to covid-19 quickly by imposing lockdowns and track-and-trace measures, the more singular exception is Finland. It had learned the cost of unpreparedness in a painful way.

In 1939 Finland was attacked by the Soviet Union, whose population was 40 times larger. Finland‘s access to help from the outside world, via the narrow outlet from the Baltic Sea, was cut off during the second world war. Finns managed to fight Soviet troops and preserve their independence—but at a terrible cost. Finns have not forgotten the war’s lessons nor the interruption of their supply routes.

On a visit in 2017 to Hietaniemi cemetery’s beautiful, sombre military section for fallen soldiers from that war, fresh flowers decorated the graves, even though more than 70 years had passed since the last burial. A Finnish visitor explained, “Every Finnish family lost family members in that war.” That memory has stayed alive. Finns remember their unpreparedness, and their losses, and the enormous odds against them, and their nevertheless surviving.

As a result, the Finns developed the concept of “total defence”. They now prepare for almost anything: war, pandemics and a range of natural and man-made disasters. The government appoints a Security Committee, which identifies critical functions of society, crises that might disrupt them and the ministry responsible for maintaining each particular function.

Four times a year, a four-week National Defence Course gives training to participants from business, media, government, churches, the security forces and non-profit groups. A National Emergency Supply Agency stockpiles (at secret locations) essential products the import of which might be blocked in a crisis. It includes fuels, grains, chemicals, industrial materials and, of course, masks. Organisations at all levels—national, regional and city—formulate preparedness plans. By law, industries must maintain stockpiles. For example, the pharmaceutical industry must maintain “excess stocks” of critical medicines.

People who worry about balancing the cost of preparation against economic efficiency may wonder: how can a country allocate funds given the unlimited potential disasters that could strike? Does preparedness cost more money upfront than it saves in the long run if disaster hits?

Finland‘s experience suggests answers. To allocate funds, Finns identified the most important dozen types of crises requiring plans, such as disruptions of the power supply, telecommunications, public health, food-supply and payments systems. They considered risks ranging from extreme weather and terrorism to the breaching of national borders. That is, Finland is prepared not just for a specific crisis, but for almost any calamity.

As for the cost, plans in themselves cost little money but save crucial time. Countries without adequate pandemic-response plans lost valuable weeks just debating what to do about covid-19. And although money is spent on stockpiling, prices are lower in normal times than in an emergency. Finland‘s stockpiles are funded by a small petrol tax, less than a penny per litre of car fuel.

Finns haven’t reverted to short-term thinking, because there are those 100,000 graves with fresh flowers to remind them of the price that they paid for unpreparedness—and because Finnish politicians exercised leadership by promoting planning. As a result, the country has among the lowest covid-19 case rate among 21 western European countries.

Of course, other countries have prepared responses to specific calamities. Japan is exceptionally ready for earthquakes, but wasn’t equipped for the Fukushima nuclear meltdown. Switzerland has nuclear bunkers, but not silos filled with facemasks. East Asian countries responded quickly to the virus based on previous experience with epidemics, not from a culture of general preparedness. The country closest to Finland’s prepare-for-anything mentality is Singapore, an island state amid big neighbours. Though it dealt quickly with covid-19’s first wave, it was caught off guard by its subsequent spread.

The big, unanswered question is how can preparation happen on a planetary scale? After all, Finland is a single country that can devise national solutions for a national crisis. Covid-19 is a global crisis, as future pandemics will be. They require international solutions. America won’t be safe if it eliminates covid-19 within its borders while the virus persists elsewhere. Will the countries of the world co-operate?

It is easy to be pessimistic. Almost all of the world’s institutions have failed us during this crisis. But future preparedness has a powerful ally: the unforgiving reality of virus transmission. Covid-19 is persuasive, and its tools include killing people around the world, devastating economies and government budgets, and causing massive unemployment.

The first wave of this merciless persuasion has barely begun in most of the developing world. Its further waves of persuasion, including inevitable tax increases, lie ahead for the industrial world. (President Donald Trump, Fox News and American beach party-goers might be unpersuaded, but the broader American electorate may be when it vote in November.)

Remember: the world already has a track record of international, collaborative success against widespread diseases. Smallpox, one of history’s worst viruses, was finally eradicated worldwide in 1979 despite the difficulty of stamping it out in Somalia, its last frontier. All countries, through the World Health Organisation, funded the campaign to eliminate smallpox there—for decent, selfish reasons: no nation was safe so long as smallpox survived there. The world also eliminated rinderpest (or “cattle plague”). It is close to eliminating polio.

Efforts like these protect everyone against threats that do not respect borders. We hope that the world after covid-19 will be like Finland, prepared for a myriad of calamities. What threats should the world prioritise? Besides pandemics, our list includes the threats that interrupt international supply chains (such as embargoes); along with droughts, natural disasters, financial crises, trade wars and political and military unrest.

Would stockpiling supplies be a waste of money? No. As many countries have now discovered, supplies may be unavailable or far more expensive in a crisis. Finns found that stockpiling even lots of essential supplies adds only trivial costs to a national budget.

If this approach is duplicated on a global scale, our planet will be better prepared. Do you have a better idea? No, you don’t: there is no good alternative.■

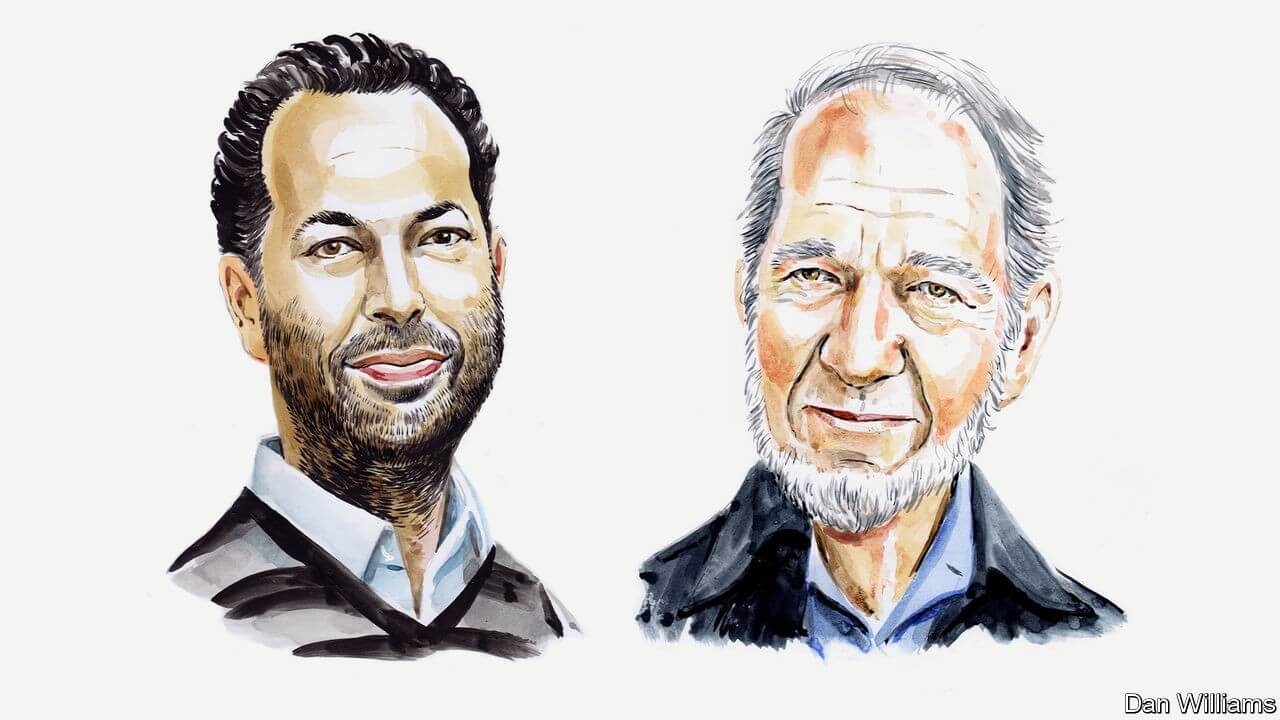

Jared Diamond, a geographer, is the author of books on development and crises of civilisations, notably “Guns Germs and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies” (Norton, 1997). Nathan Wolfe, a virologist, is the founder of Metabiota, an epidemic risk analytics firm, and author of “The Viral Storm: The Dawn of a New Pandemic Age” (Times Books, 2011).